Blog 11

4th – 7th May

Moynaq to Nukus

Distance: 256km

Total Distance: 2855km

In Moynaq I arranged for a guide to be with us for the remainder of the way to Nukus. Khurmet, whom we had met at the Yurt Camp beside the Aral Sea, was the perfect choice because he has local roots and is extremely knowledgeable about the environmental, historical and social issues related to Moynaq and the Aral Sea.

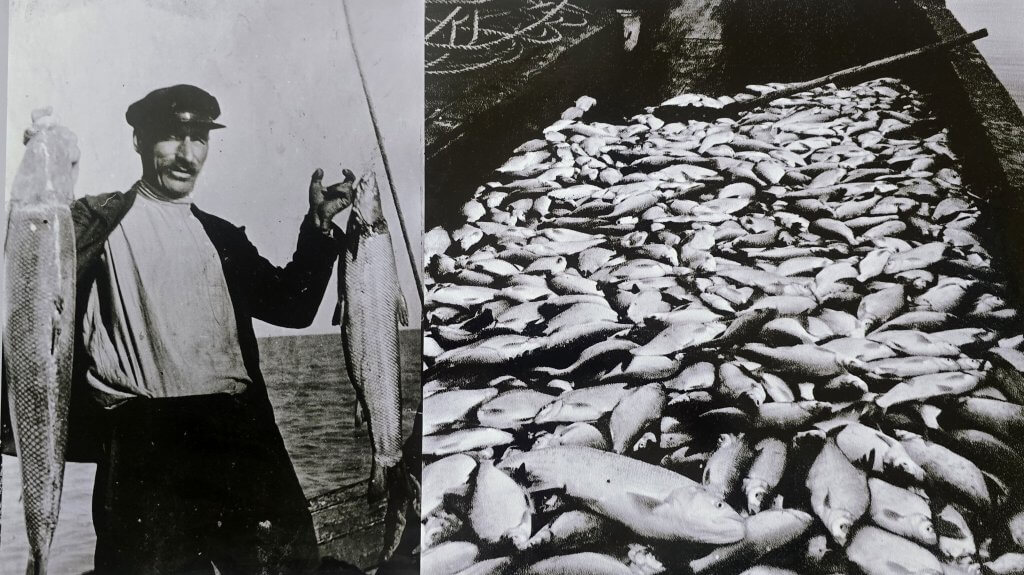

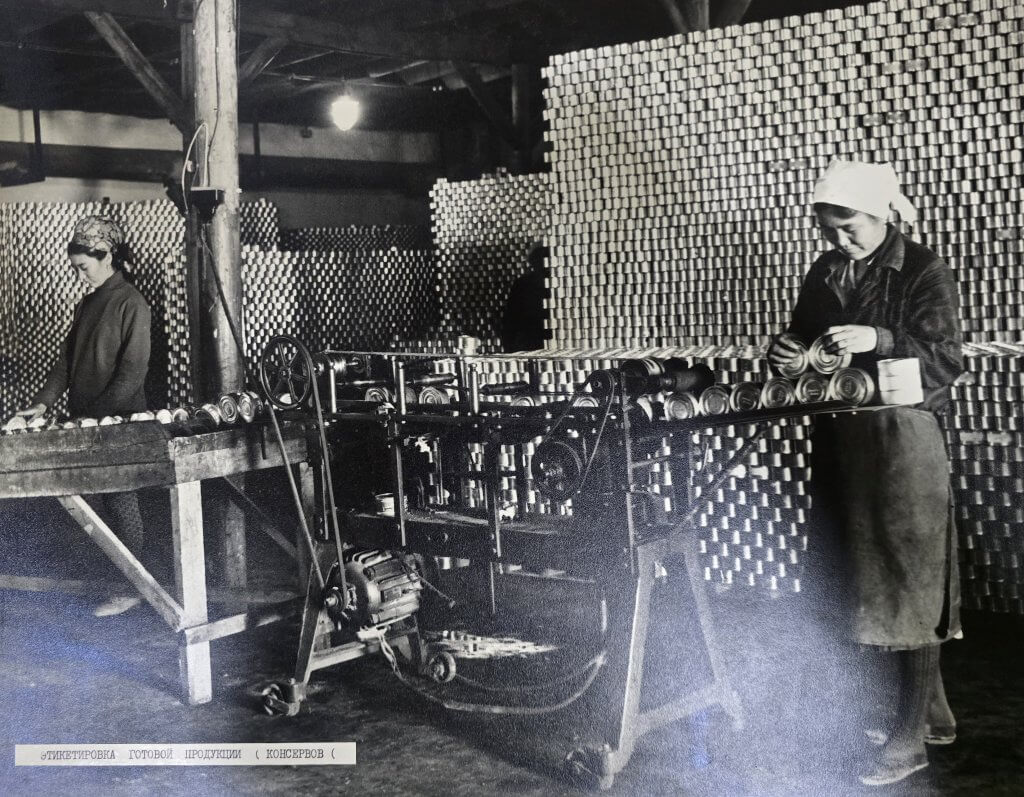

While Aralsk was the major Aral Sea port in the north, Moynaq was formerly the key port city in the south. Separated by 475km, it was a significant expedition to sail between the two. The effects of the drying of the Aral Sea have been catastrophic in Moynaq and the whole region. Moynaq was on an island, the original harbour was 13km away. When water first receded from the harbour, the 600-strong fleet of ships moved to Moynaq. The town was booming with fish processing factories and other businesses and a population of around 30,000; 100,000 regional residents.

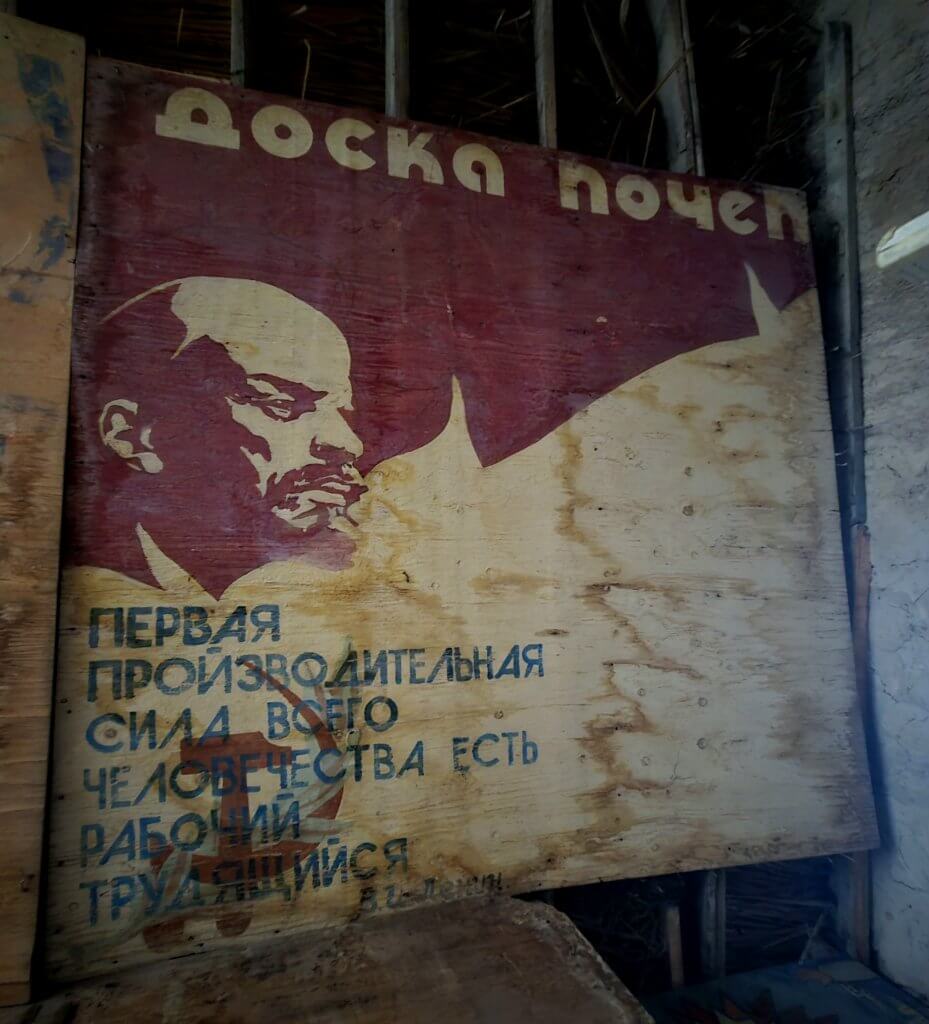

The Soviet regime’s short-sighted justification for deliberately draining the Aral Sea was implemented by way of a crazy economic deduction. By some weird calculation they costed “the value” of fishing in the Aral Sea versus the much higher profits from cotton production. Combined with the infamous propaganda machine, the Aral Sea’s fate was sealed.

The Soviet Union’s insatiable drive for cotton was not only for producing textiles, they had secretly discovered how to make gunpowder from cotton pulp. The gunpowder has been used to fire weapons in its 20th Century conflicts. Since the break up of the Soviet Union, Uzbekistan and Kazakstan have continued to sell cotton to Russia – over 98 percent of Russia’s imported cotton pulp for the past decade – and the trade has grown since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Both Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have officially remained neutral with regard to the Ukraine war, and they understandably must tread a diplomatic and economic tightrope when it comes to relations with Russia.

Khurmet took us to see the famous boat cemetery on the edge of town. The graveyard of 13 ships lies on the old seabed at the base of the coastline. Looking out over the sea of sand, low vegetation and salt, it was difficult to comprehend that water still lapped the banks in the early 1980s. The larger fishing trawlers would have gone by then, only smaller boats could have docked.

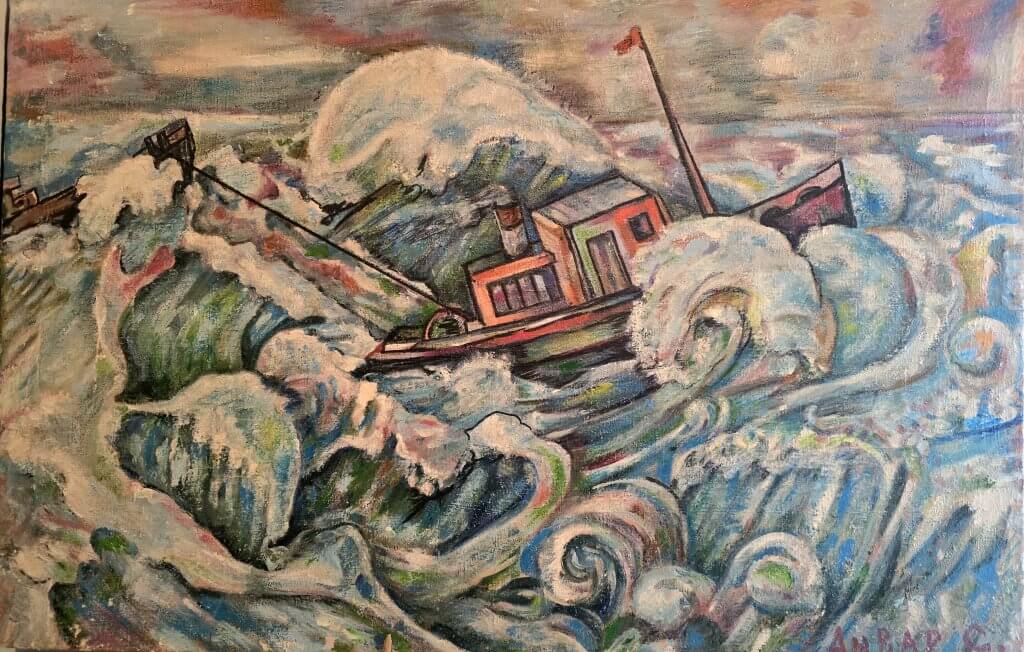

I decided to take an extra day in Moynaq so Khurmet could take us to meet an old fisherman who remembers what life was like to grow up beside the sea and live off its bounty. The sailor, Anvar Sagimbetov, always wanted to be the captain of the boat he crewed as second in charge. In 1966, he was conscripted to the Soviet army for three years and when he returned in 1969, he found his boat grounded – the receding sea had become too shallow for larger boats. He lived in hope that this problem was temporary, but as we know, the water never came back.

Anvar retrained as a teacher and then as an artist. He is very talented and has spent his days bringing to life memories of the golden days as a boy and fisherman, recording Karakalpak history and culture, and illustrating Moynaq in the present – the Aralkum Desert, people’s emotions, sadness, cultural change and what he foresees the future might be like.

Anvar’s grandson, who works as a technician, was affected at birth by the dust. The toxic salt affected bone metabolism and has caused significant deformities, particularly on his left side. Bone issues are one of the most common afflictions caused by the toxicity. Birth defects, miscarriages, an increase in cancer rates, respiratory problems and a shortened life expectancy are some of the other key health issues.

Moynaq is trying to adapt, revitalise its culture and develop an economy based around tourism. There is a lot of development going on, an impressive museum, and the STIHIA Electronic Music, Arts and Science Festival.

Day 43

Moynaq to Kazakdarya: 120km

Back on the road, my first objective was the ride the 45km to Porlatau, retracing part of my route in to Moynaq, and then turning east and into a ferocious, dry headwind that whipped dust straight off the desert. Over the final 10km, there was welcome respite in the form of the Sokaral Reservoir. The road was shaded by the last stands of an endemic variety of poplar trees – the first significant trees I’d seen for quite a while. Adding water and trees reduced the temperature significantly and we stopped to make the most of the idyllic, cooler location. The Sokaral Reservoir basically holds the last of the Amu Darya’s water, which is contained for the local people to make a living.

Five kilometres on I reached Porlatau and beyond the village, it felt like armageddon! It was desolate and gusts of hot, dry wind stirred the dust. This is the scene of where the Amu Darya, Central Asia’s biggest river, dies. I stopped midway over the 500m long causeway. Judging by the size of the banks, the river was enormous. The Amu Darya’s flow was much bigger than the Syr Darya’s. I was told it was over 100m deep at the point where I stood. Occasionally a small amount of water flows this far, but it is immediately lost, evaporating or disappearing into the desert sand, leaving the toxic salt to crystallise on the ground. I felt very emotional, that the majestic river could come to this – and it was all due to shortsighted human intervention, economic greed and in post-Soviet times, not enough collaboration.

On the other side of the causeway, there was a huge project underway to build new banks in the hope of saving the last drops of water when it does come, to increase the size of the Sokaral Reservoir for the nearby communities.

From here we followed a labyrinth of banks, some built recently, others by the Soviets back in the late 1980s – all to manipulate the Amu Darya’s flow and hold more of the water.

Navigating our way along the banks and lakes, our route took us to the Amu Darya, however we came to a point where it was too overgrown for the support vehicle to traverse. There was just one section of about 1.5 kilometres, according to Khurmet, where I should be able to slip through on the bike. The vehicle would go the long way round and meet me where my track came out. I set off and immediately I could see why the support vehicle would have been able to get through. It was a brilliant little track, very overgrown in places. Khurmet mentioned I should try to veer left at some point to meet up with the road they were to take, but there were no obvious turnoffs. After about 2.5km, I ended up at the river. The track stopped there. I had noticed a possible left hand trail, returned to that point and followed it for nearly a kilometre, essentially bush-whacking along what could have been a trail. But this soon disappeared completely. With no other choices, I decided to retrace my path to where we separated.

Now I was really worried. I didn’t have much water and no food left, and didn’t know exactly where they had gone. A couple of fishermen on a motorbike stopped and we spent ages trying to communicate the situation. In the end, I had noted what was almost certainly the fresh tyre tracks of the support vehicle and followed them. It started off in the right direction but then veered the wrong way. With no choice, I kept following the track. A few kilometres later, I saw what could have been a car coming towards me in the distance, giving me hope. But as the vehicle drew nearer, I could make out a small fishing boat being carried by two guys on a motorbike with a side car! Another pair of motorcyclists stopped and we established that they had seem our 4WD. I was in the process of sketching the support vehicle on the ground when we spotted my team across on another bank. I took off, cycling cross-country directly towards them in case they hadn’t seen me, about 500m away. We were soon reunited and all very relieved. They were just as worried.

This episode used up a lot of time. We made a solid plan to keep together and work our way through the network of rough tracks to a made road – well it was once a Soviet-made asphalt strip, but hadn’t been upgraded since. It was a terrible cycling surface of broken asphalt sealed with big stones. I pushed into a side-cross wind, reaching Kazakdarya, a further 42km on, at last light. Then a further five kilometres on a rough track to a yurt camp with a natural spring. Frustratingly, we again lost each other and reunited at the venue – of course, no sign posts.

Day 44

Kazakdarya to Nukus: 136km

From Shimbay, the road became a busy highway and I pushed hard to reach Nukus, a day earlier than my original plan. As this journey is about exploring life along the Amu Darya, I was guided through the city to the river.

The finale to this section was, after cycling in the dark through Nukus for about 7km to reach the Jipek Joli Art Hotel, where we stayed, Ayjamal had secretly arranged a champagne reception with a few supporters and staff/team to celebrate the journey.

By the way, I do love reading everyone’s comments – I just can’t reply effectively, unless you go back to the post – comments don’t come to your email.

FOLLOW THE JOURNEY

Thanks to ZeroSixZero, you can open this URL on your phone and select “add to home screen” and the map will become and app. You can then keep updated in real time: https://z6z.co/breakingthecycle/central-asia

TAKE ACTION

Support my Water.org fundraiser to help bring safe drinking water and sanitation to the world: Just $5 (USD) provides someone with safe drinking water or access to sanitation, and every $5 donated to my fundraiser will enter the donor into the Breaking the Cycle Prize Draw. https://give.water.org/f/breakingthecycle/#

EDUCATION

An education programme in partnership with Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants, with contributions from The Royal Geographical Society and The Duke of Edinburgh’s International Award Australia. We have created a Story Map resource to anchor the programme where presentations and updates will be added as we go.

Wow another amazing read from another amazing adventure Kate. Wishing you happy & safe travels

Hi Kate and team,

More inspiring stories of your endeavour. Many thanks. The blog really carries me with you on this journey. It is a journey that very few if any have made in such detail. The dust problem is very little known outside the area. Photos of the artists work also valuable as a record.

No mention of the health issues; can I assume they are solved?

I am looking at Afghan visa issues; it may be that these have become easier. I have advice from a group called Untamed Borders, who have been helpful.

You and your team are an inspiration. Well done.