Blog 15

27th May -1st June

Merv to Bukhara

Distance: 404km

Total Distance: 4344km

The Zerafshan-Karakum Corridor – Stage 1

Arising in the mountains of Tajikistan, the Zerafshan River gushes down to the steppe, and passes through the legendary city of Samarkand where much of its water is taken up by the Dargom Canal. Samarkand, Bukhara and all towns along its route are totally reliant on the Zerafshan’s water. Once a key tributary of the Amu Darya, the river whose name translates to “the spreader of gold” no longer makes it. The last drops disappear into desert sand just before Turkmenabat.

Within the vast network of trails that make up the Silk Roads, the Zerafshan-Karakum Corridor is perhaps the most important hub. Routes from every direction converged here, leading to the establishment of some of history’s grandest cities.

Stretching across a distance of almost 900 kilometres, the Zerafshan-Karakum Corridor was a melting pot of ethnicities, where people from across the world brought their own cultural influences, and where powerful empires left their mark. For almost two millennia, from the 2nd century BCE to the 16th century CE, the corridor evolved, not only as a trading route, but also one of the most important places in the world for the exchange of cultures and artistic and scientific ideas.

My plan is to follow the entire Zerafshan-Karakum Corridor from Merv Oasis, firstly tracing the ancient caravan roads across the Karakum Desert to Turkmenabat (Amul). Continuing in Uzbekistan, I will follow the fertile Zerafshan valley through Bukhara to Samarkand. Finally I will divert into the mountains of Tajikistan to complete the route. Khisorak Fortress, 275km from Samarkand, acts as a bookend to the 34 sites that make up UNESCO’s 2023 World Heritage inscription.

Merv

The ruins of the ancient city of Merv existed between the 3rd millennium BCE and the 18th century CE, about 4000 years. At its peak in the 12th century CE, Merv was one of the largest and most cosmopolitan cities in the world with a population of over half a million. I was very keen to explore the ancient site as I had been aware of Merv – a legendary Silk Roads city – for many years.

Adjacent to the UNESCO World Heritage Site, hidden away amongst a grove of shady apricot trees, we enjoyed breakfast at a small visitors’ museum and centre. One of the attractions was a Turkmen horse, a special breed from the region called Akhal-Teke. They have a reputation for speed and endurance, intelligence, thin manes and a distinctive metallic sheen. These horses are adapted to severe climatic conditions and are thought to be one of the oldest existing breeds. Most of the 6,600 Akhal-Tekes in the world are in Turkmenistan. Akhal-Teke horses, along with Alabay dogs and the craft of traditional carpet making are the three definitive treasures of Turkmenistan.

From there we walked across to the most well-known ruin in Merv, the Great Kyz Kala. Built in the 9th century, Kyz Kala was an elite palatial suburban residence, perhaps meant for the use of the governor of Merv.

Excavations have been carried out inside the brick and adobe building, but archeologists are at a point where they cannot do much more without risking collapse. Our guide explained that the longevity of the structure was due to the shape of its construction. Its walls are angled slightly inward and narrower at the top to allow water runoff. The octagonal half-columns add strength and also make it more resistant to weathering.

Day 65 – Merv to Zahmet – 47km

After exploring Merv, I was looking forward to start a new phase of the expedition, to cycle the length of the Zerafshan-Karakum Corridor. I was not going to be able to see all 34 sites over the 1000km, but I hoped to include several that are typical of each region; the deserts, along the Zerafshan Valley and canals and into the mountains, through Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and into Tajikistan.

The first stage was to follow the caravan route from Merv and across the Karakum Desert to Amul/Turkmenabat. Setting off from the Great Kyz Kala, I pedalled 5km through the World Heritage Site and then out into the heavy traffic. There is no longer a track tracing the ancient caravan route directly from Merv. I had to follow the main highway most of the way with a diversion into the desert in search of some of the caravanserais that once serviced weary Silk Road travellers on their arduous journey across the desert.

The highway was horrific – both the road and the wind conditions. The asphalt was riddled with giant potholes, crumbling edges and lumpy repairs. The headwind carried dust so thick it was difficult to breathe or even see the continuous stream of trucks in front of me as they emerged from the “mist”. I was knocked down to about 13km/hr. The trucks were forced to travel as slowly as me, in fact, I regularly passed some of them. There was a second gravel road that some drivers used, stirring more dust. No vehicle could travel fast and all drivers shared the road, slaloming from one side to the other, sometimes along the gravel verge. It was a free for all but I didn’t feel too intimidated because everyone was watching out for each other. It took me about three hours to do 47km to Zahmet which I covered in the late afternoon. We stayed at a truck stop cafe – a rough place with no official accommodation. The owner gave up her room for Anna and I as there was nowhere else available to stay.

Day 66 – Along the Caravanserai Route – 80km

This was a day I was looking forward to, even though it promised to be a difficult one in the sand desert. I covered a further 24km on the highway before reaching a gravel turn off. Pretty soon I was following a sandy track, managing the small dunes reasonably well with my 3″ wide MTB tyres – a proper fatbike would have been the ticket here. After crossing a few sand ridges we entered a wide valley between the dunes. After 13km on the track, the first caravanserai emerged above the low scrub and sand dunes.

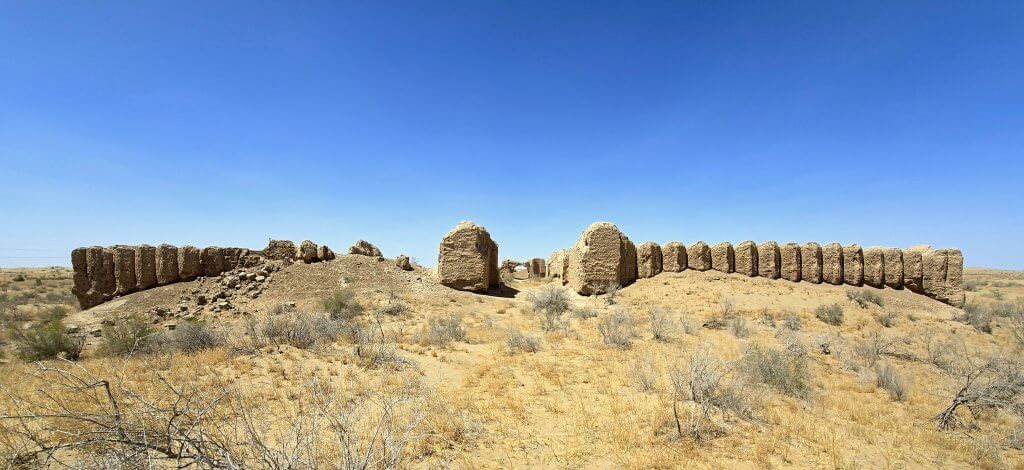

It was Gyzylja Gala Caravanserai, which was made up of two separate walled courtyards about 80 metres apart. Each one was a rough square with approximately 55-metre sides that had rooms around the inside of the walls. I could make out some of the main fortifications of the caravanserai but there is nothing left of the interior, just fragments of ceramic pots and jars everywhere.

Just 6km of sand dunes further on was the best preserved caravanserai, Akja Gala, which was in use from the 9th to the 12th century. Rectangular in shape it was bigger than Gyzylja Gala; about 150 metres long and 80 metres wide.

Another 5km along the route, a different type of ruin, Tahmalaj, which was a rest stop called a köshk (from which the English word ‘kiosk’ is derived). It was much smaller than the nearby caravanserai and would have been used by a different type of traveller.

After Tahmalaj there was a long 20km stretch, once we found our way, of bigger, softer sand dunes. It was very hard work. The sand seemed more fluid in the afternoon heat. I was pretty exhausted by the time we reached the final caravanserai, Konegala. There is very little of this kala left, just a few pieces of the outer walls. It covered a massive area, I estimate about 200 metres in length, but like Gyzylja Gala , there was little to photograph.

At this point I’d reached the asphalt road that after 10km led us back to the highway. From the highway, we drove to a town with a hotel for us to stay in (our support team were not equipped to camp). It was an incredibly rewarding day because it felt like there was always something new to discover, fossicking around the ruins, trying to picture what they would have been like in their heyday.

Days 67, 68 – To Turkmenabat, Farap border crossing to Olot – 123km, 57km

The following morning we returned to the point where I stopped. I was taking the “fast route” (compared to a camel caravan) across the Karakum Desert, the dreaded highway to Turkmenabat, 123km away. It was a long, hot day but fortunately only gentle resistance from the headwind. I found I could move a little faster over the asphalt, even though it was very rough in many places. We stopped to visit Repetek Biosphere Reserve, a kilometre off the highway, but there was little to see. Everything was closed. The weather station there is where it was determined that Repetek is the hottest place in Central Asia.

I needed to reach Turkmenabat on 29th May because we had to leave the country the following day. There was much to organise before we left and we were again slightly anxious about the border crossing. From Turkmenabat, we took a few short cuts, a 30km route through the backstreets and over the Amu Darya for the last time in Turkmenistan. Passing about 4km of stationery trucks we finally reached the first checkpoint where Anna and I said goodbye to Oraz and Atash. Our crossing went smoothly – firstly a bus ride for Anna with all of our gear while I cycled to the Turkmenistan passport control and customs, then another ride to a middle passport control and identification, then a longer cycle/bus ride to the Uzbekistan side, more passport checks and baggage scans, a few questions and we were free to go.

I had employed Sasha, our driver from Kazakhstan, to cover this next section but unfortunately he was held up for 15 hours waiting to cross from Kazakhstan into Uzbekistan and then had a huge drive to reach the Turkmenistan border. He couldn’t make it in time so we hired a taxi to take us to the nearest town with a hotel – Olot, 27km from the border. The driver did a good job supporting my ride during the afternoon and ensuring we were accepted into hotel accommodation.

Olot to Bukhara – 98km

Sasha drove through the night and was in Olot waiting for us by 8am the next day. It was great to have him back on the expedition. He was exhausted but there was only one day’s ride for him to support to reach Bukhara where we planned to have a rest stop.

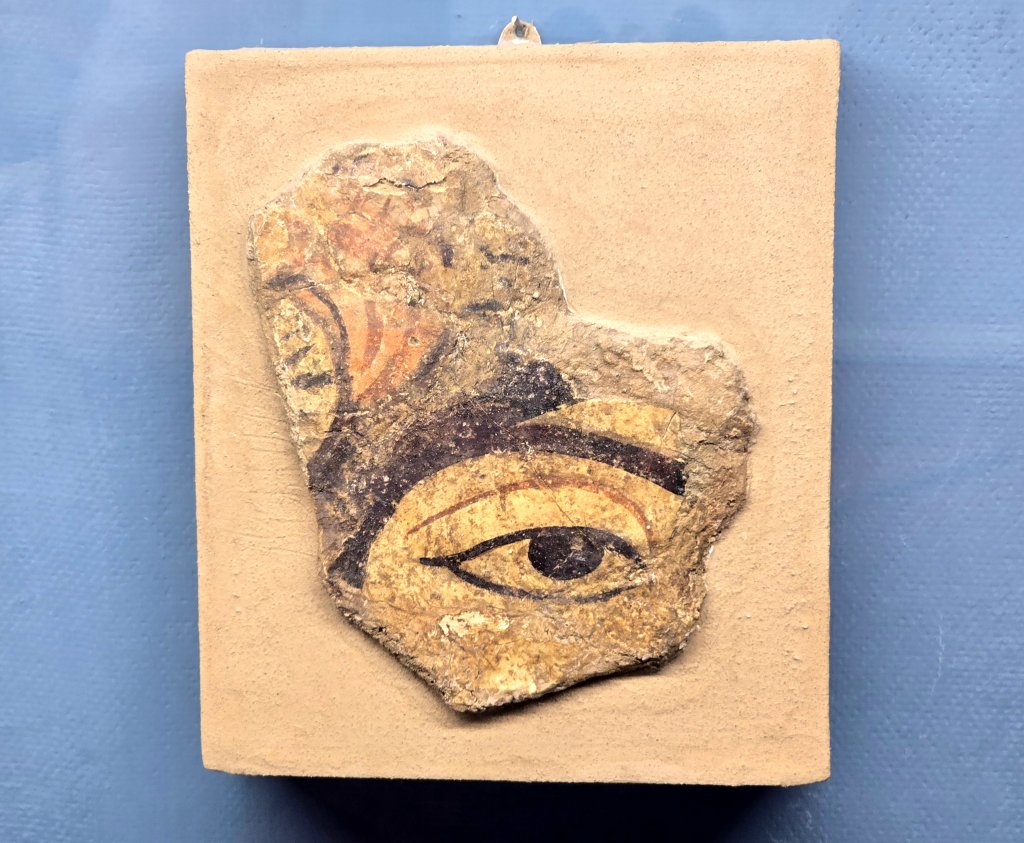

About 30km north of Olot is one of the most significant sites of the Zerafshan-Karakum Corridor, the ancient town Paikend, which dates back to the 4th Century BCE – 12th Century BC. We first visited an excellent little museum that outlined the history of the settlement and contained many artefacts discovered on the site.

The Paikent historical museum built near the site in 2003 shows the unique artefacts discovered at the site: tableware, ceramics, glass, Chinese and Japanese porcelains, jewellery and coins dating from the 2nd – 9th C.

Paikend existed until the Zerafshan River changed its course in the 12th century. The water supply dwindled and its residents left. By the 13th century Paikend was buried under the sands of the Kyzylkum Desert. For many centuries the evidence of the town’s wealth and prosperity was kept under a thick blanket of sand. The archeologist who excavated Paykend in the 1980s discovered it was in excellent condition, as if it had been conserved on purpose.

I pushed through another extremely hot day (37C) and arrived in Bukhara ready for a rest after an intense couple of weeks in Turkmenistan.

The wonderful city of Bukhara will feature in the next blog.

IA big thank you to Oraz (guide), Atash (driver) and the supporting company, Stan Trips for making it possible to travel through Turkmenistan. My requests for this journey were far from regular and they did a great job working through the constant controls and paperwork before, during and after this leg of the expedition.

FOLLOW THE JOURNEY

Thanks to ZeroSixZero, you can open this URL on your phone and select “add to home screen” and the map will become and app. You can then keep updated in real time: https://z6z.co/breakingthecycle/central-asia

TAKE ACTION

Support my Water.org fundraiser to help bring safe drinking water and sanitation to the world: Just $5 (USD) provides someone with safe drinking water or access to sanitation, and every $5 donated to my fundraiser will enter the donor into the Breaking the Cycle Prize Draw. https://give.water.org/f/breakingthecycle/#

EDUCATION

An education programme in partnership with Exploring by the Seat of Your Pants, with contributions from The Royal Geographical Society and The Duke of Edinburgh’s International Award Australia. We have created a Story Map resource to anchor the programme where presentations and updates will be added as we go.

Hi Kate and team; you are right there is one of the highlight areas of your whole journey. Thanks for the historical context and photos. More of the wonderful Bokhara expected soon. It really was a sort of 19th C mystery city (like Lhasa) , made all the more feared and celebrated by the stories of Stoddart and Connolly in the ‘Bug Pit’ and their eventual execution. So when Alexander Burnes finally made it there, he was treated back in UK as a conquering here.

Thanks for keeping us involved in this memorable journey.